【mabokov按】“儿童文学中10大经典人物形象”转载自《卫报》。作为资料收藏。

Pippi Longstocking from The Adventures of Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren

Pippi Longstocking from The Adventures of Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren

Also known as Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Ephraim’s Daughter Longstocking, this nine-year-old Swede is a rebel and an eccentric who strides about town in a pair of man’s shoes and is possessed of a strength so formidable that she can lift her horse. She lives free of adults and their rules in a house with her pet monkey, said horse and a suitcase full of gold. A thrilling naughtiness, particularly towards the more exasperating breed of adult, is tempered by a pronounced sense of fair play. A powerful defender of the weak and oppressed, she introduces her two young friends to realms beyond the conventions of 1940s village life

Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery

Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery

Despite a brutal upbringing, Anne Shirley, an orphan sent to live with a sibling couple on Prince Edward Island in Canada, has an infectious appreciation for the beauties of life. She is a dreamer whose fantasies land her in unusual predicaments that appal the local worthies in this early 20th-century community. Kindness, courage and relentless optimism can make for a bland read, but Anne’s headstrong nature and garrulousness attract enough trouble to keep her winsome throughout the nine books in the series.

Matilda Wormwood from Matilda by Roald Dahl

Matilda Wormwood from Matilda by Roald Dahl

At the age of six she has read her way through her local children’s library and embarked upon Dickens, Orwell and Austen. This formidable intellect is unappreciated by her parents, who compel her to watch more television, and by her brutal headteacher, who is inclined to fling irritating children out of windows. And so her frustrated genius finds outlet in telekinetic powers that can usefully torment said headteacher with invisibly guided newts and chalk. The precociousness is softened by childish mischief – she takes imaginative revenge on her parents – and by fearless loyalty to the one person who shows her sympathy.

George from George Speaks by Dick King Smith

George from George Speaks by Dick King Smith

At the age of four weeks, George utters his first syllables. Not infant gurgles but stern, fluent, adult loquaciousness. His skills are revealed only to his older sister Laura. He helps her with her homework and in return she assists him with the challenges of babyhood. He is crafty – he uses Laura to manipulate his parents – and intelligent, but also caring and sensitive. When on his first birthday he delivers a speech to his startled family, Laura asks if he would like to be a judge or a lawyer. His ambition, though, is to write stories for other children to enjoy.

Tracy Beaker from The Story of Tracy Beaker by Jacqueline Wilson

Tracy Beaker from The Story of Tracy Beaker by Jacqueline Wilson

Superficially this is the “autobiography” of a graceless 10-year-old with behavioural problems. Tracy, abandoned by her mother, lives in a children’s home and has been rejected by the two couples who try to foster her. She is sulky, vengeful and prone to tall stories. Underneath is a vulnerable little girl who eagerly responds to any show of affection and who invents fantasy worlds to cope with her own grim reality.

Lyra Belacqua from His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman

Lyra Belacqua from His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman

A lack of conventional storybook charm makes this 11-year-old instantly arresting. Raised as an orphan by the staff of a fictional Oxford college in a parallel universe to our own, she is unruly, quick-witted and cunning. She is also an accomplished liar. A witches’ prophecy declares her “destined to bring about the end of destiny” and, after a fashion she does, liberating innumerable souls during her adventures. A second Eve, her Fall brings happier consequences than her biblical counterpart and reveals her pluck, resourcefulness and almost supernatural intuition. She is, at the end, prepared to sacrifice her alter ego/daemon to keep a promise to rescue a friend.

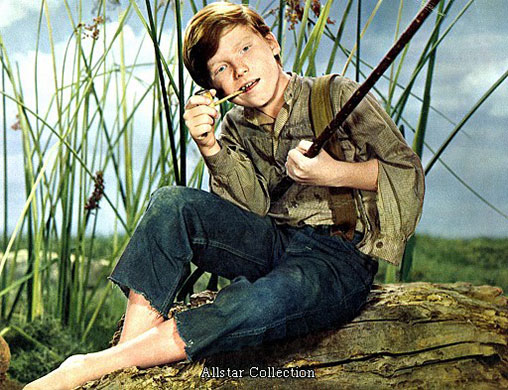

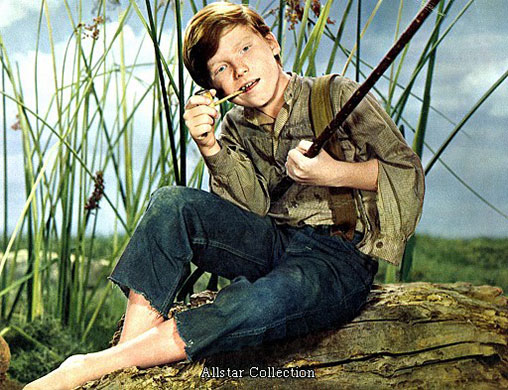

Huckleberry Finn from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Huckleberry Finn from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Twain reckoned it an account of how “a sound heart and a deformed conscience come into collision and conscience suffers defeat”. Huck, son of a drunkard in America’s deep south is introduced in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer as Tom’s friend and conspirator in a series of madcap adventures. In his own tale he develops into a challenger of early 19th-century mores. As he and the fugitive slave Jim flee down the Mississippi, Huck reassesses his racial prejudices and ignores his civic “duty” to turn Jim in.

Petrova Fossil from Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild

Petrova Fossil from Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild

She is one of three abandoned babies salvaged by a scatty geologist and sent (in Petrova’s case by the Russian postal service) to be brought up by his long-suffering great niece. Petrova is the only one of the trio who is not naturally enraptured by the arts (engines are her passion), but she gamely takes to the stage to help supplement the family’s dwindling income. She is industrious, honest and giving and embraces her fate with good humour while nurturing her real ambition to be a pilot.

William Brown from Just William by Richmal Crompton

William Brown from Just William by Richmal Crompton

Grubby, irreverent and accident-prone, William is a rascal with a conscience. He turns a temperance meeting into a punch-up, wrecks the love life of his elder siblings and, due to a misunderstanding of a double negative, throws a wild party in his parents’ absence. His intentions, however, are usually kindly. Ever since he and his band of Outlaws burst into the nation’s consciousness in the 1920s he has come to embody an ideal of boyhood.

Sara Crewe from A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Sara Crewe from A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett

A Cinderella figure who embodies Victorian saintliness in the face of adversity. At seven Sara is pampered by her father who demands the priciest luxuries from the boarding school at which he enrolls her. Privilege, however, fails to corrupt her. She is intelligent and good humoured with an infectious warmth that embraces the lowliest of her new acquaintances. The sunshine continues when impoverishment and drudgery befall her and she relies on her private fantasies to preserve her natural zest for life. Her selflessness naturally ensures a cheerful destiny.

【Link】

Pippi Longstocking from The Adventures of Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren

Pippi Longstocking from The Adventures of Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery

Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery Matilda Wormwood from Matilda by Roald Dahl

Matilda Wormwood from Matilda by Roald Dahl George from George Speaks by Dick King Smith

George from George Speaks by Dick King Smith Tracy Beaker from The Story of Tracy Beaker by Jacqueline Wilson

Tracy Beaker from The Story of Tracy Beaker by Jacqueline Wilson Lyra Belacqua from His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman

Lyra Belacqua from His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman Huckleberry Finn from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Huckleberry Finn from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Petrova Fossil from Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild

Petrova Fossil from Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild William Brown from Just William by Richmal Crompton

William Brown from Just William by Richmal Crompton Sara Crewe from A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Sara Crewe from A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett